art

Pablo Edelstein, sculptor.

Seven decades of artistic study, teaching, experimentation and commitment

Pablo Edelstein was recognised in Argentina’s art world pri-marily as a sculptor, most notably for his ceramic works. From the mid-1940s until his death, Edelstein was involved in the art community for seven decades, from his early in-clusion in the important Buenos Aires galleries, his close affiliation with prominent artists and theorists, and also as a teacher and champion of the institutionalisation of ceramic art. Throughout his career his production primarily centred mostly on the human form – predominantly the female fig-ure – but also animals and landscapes, and later included his explorations of the Moebius strip. Acquiring a general knowledge of art history, particularly of vanguard move-ments and artists, during his European upbringing and youth, Pablo much later became involved with prominent artists in Argentina, some of whom were active in disrupt-ing the local art scene.

Despite a lifelong devotion to figurative art, he never hesi-tated in pushing its limits to the threshold of abstraction, an impulse driven by his ceaseless desire to experiment with materials. Likewise, process and technique are what moti-vated his study, work and teaching.

The beginnings: his training and initiation

After renouncing a life of ranching, he settled in the city of Buenos Aires in 1944 with the firm intent of embarking on an artistic path. “At the age of 27, I passionately and en-ergetically dove into it so I could express myself through this medium”. 1Although Edelstein had attended art class-es while simultaneously studying agriculture, he received his principal grounding at a very young age from the visual stimulation of his visits to various museums in Europe and a vast collection of art books inherited from his mother.

Due to moving and not completing his studies in Argen-tina, Edelstein was unable to enroll in the country’s offi-cial Fine Arts schools. This, however, proved not to be an impediment in starting local instruction. His first step was to complete two years of instruction at the studio of Jorge Larco, the renowned watercolourist and well-regarded set designer.2

On Larco’s recommendation, Pablo enrolled in the Escuela Libre de Artes Plásticas Altamira,3 also called the Altamira Academy. This school, which was independent from the government-sponsored institutions, brought together a faculty comprised of Jorge Romero Brest, art history and aesthetics, Brest’s brother Antonio, artistic anatomy, Jorge Larco, watercolour, Raúl Soldi, painting, Lucio Fontana, sculpture, plus Emilio Pettoruti and Laerte Baldini.4

Edelstein participated at the periphery of academic training, paradoxically allowing him to be in the midst of the artists and intellectuals who would form the era’s avant-garde.

It was at this institution, particularly in the sculpture work-shop that Pablo attended, where a copy of the Manifiesto Blanco, White Manifesto, circulated for the first time, which was an antecedent of Lucio Fontana’s Spatialist manifes-tos. As Vilma Villaverde recalled, Lucio Fontana created “abstract ceramics” in 1930, later leading him to the 1946 Manifiesto Blanco.5 The manifesto was signed by everyone except Fontana and Edelstein. The latter contending that he did not feel he was mature enough to support it and did not want to commit to other people’s thoughts.

“Seeing Fontana work, I became aware for the first time of the importance of the gestural technique”, Pablo recalled, noting that in classes, the teacher worked alongside his stu-dents while discussing art, a method he would adopt years later in his sculpture classes.

It was within this context that Edelstein became passionate about ceramics, clay and earth.

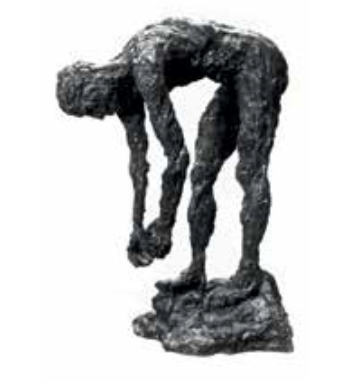

During these years he sculpted Agnes (Seated Wom-an,1946) and El labrador (The Cultivator, 1948), where the texture remained rough-hewn, without a polished finish, exhibiting the simplicity of the material and the imprints of the artist’s own labour.

Gestural technique in art.

A signature lesson from Lucio Fontana, his friend and teacher.

Edelstein began experimenting in this noble but not always entirely valued discipline at a time that coincided with the emerging field of professional ceramics in Argentina. It was only in the 1930s that the first ceramics school was founded by the Spanish ceramist Fernando Arranz.6

Shortly after the closure of the Altamira school, Fontana moved to Milan, where he planned to stay for a year but where he remained until his death. Edelstein and Fon-tana corresponded for almost 20 years, even sharing a few months together in Italy. Their friendship and disci-ple-teacher relationship continued until Fontana’s passing.

As Pablo said of their relationship, “I would like to em-phasise that the moment I met Lucio, I was certain that I had found a teacher and fatherly figure in whose compa-ny I would receive unexpected lessons and revelations”.7 On many occasions, their exchange of letters served as a long-distance artistic clinic, also constituting a chronicle of that period.

In their first letters dating from 1949, they exchanged specif-ic questions about ceramics with regard to the use of glazes, he smoke-firing technique, pigment colours, finishes and lustre, also commenting on significant exhibitions, publications, Argentine artists visiting Italy, and exchanging news of mutual friends such as Raúl Soldi and Santiago Cogorno.8 They also discussed art more generally, the future of their own efforts, the artistic environment in Buenos Aires,

the salons, gallery exhibitions, and sent each other press

clippings, books and photos.

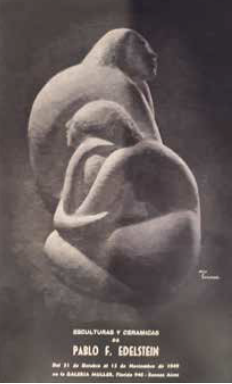

That same year, Pablo exhibited at the Müller Gallery for the second time. His inclusion to the galleries that were beginning to concentrate in the centre of Buenos Aires was speedy when taking into consideration that he hadn’t begun his art career until 1944. Edelstein wrote the text of the

catalogue, establishing his position as an artist by saying:

“Living with ART is LIVING consciously, it is to live trans forming and being transformed.” On this occasion he presented 29 works, including plasters, bronzes and ceramics. Upon receiving the exhibition catalogue, Fontana was happy with his student’s strides and the progress of his technique: “I see that you have become a true ceramic artist. You know that I do not know much about the technique, I am far more interested in the sculptural outcome of ceramics.” 9

The exhibition at the Müller gallery received very good reviews and, as a result, several students enrolled in Edelstein’s workshop the start of what would be his extensive teaching career. Years later, in 1957, he became a professor at the Escuela de Bellas Artes Manuel Belgrano, later serving as head of the Sculpture department for 30 years.10

The letters from the early 1950s revolve around the Premio Palanza award, as Fontana was invited to participate and Edelstein was in charge of managing the participation logistics, including receiving the award on behalf of his friend. Meanwhile, his work was intensive and his ceramics multiplied. His gestural technique is visible in the application of the clay, achieving a rusticity that enhances the tactile quality of the material. Themes were repeated, allowing the artist an excuse to experiment. Musculature or “living architecture”, as Pablo put it, whether of bulls or horses (so well known to him from his years as an agronomist), and human anatomy were the means to interweave shapes and textures.

On March 19th, 1951, Edelstein embarked on a trip to Italy to visit Fontana.

Pablo returned to Argentina with great expectations of applying what he had learned in Italy, where he met friends of Fontana who were ceramicists, such as Tullio Mazzotti and Agenore Fabbri. Among his most treasured memories of the trip was his visit to the Grenoble Museum in Paris and the opportunity to see Georges Rouault’s ceramics. And, importantly, he returned with the objective of opening a mosaic tile factory, for which a visit to the Ceramica Joo factory in Milan helped him learn more about the field. In 1954, Edelstein managed to open his factory in Bou-logne, in Buenos Aires province, and bring his “informalist painting” – as the artist defined it – La Cascada (The Waterfall, 1962), a grand mosaic work, to the façade of the building located at the intersection of José Hernández and Arribeños streets in the Belgrano neighbourhood of the city. The composition of the building wall’s overlay of blue hues and gradient shades forms a great tapestry reminiscent of the profound geometric works of Alejandro Puente and César Paternosto, where the patterns of our pre-Columbian roots are recaptured.

In addition to venturing into ceramic tile manufacturing, his commitment to the discipline led to his involvement in the Centro Argentino de Arte Cerámico, the Argentine Centre for Ceramic Art, as a founding and honorary member of the institution, whose primary objective was to bring together ceramic artists and create a national gallery of ceramic art.11 He participated as a juror for the Primer Salón Anual de Arte Cerámico art competition in 1958.

The 1960s and 1970s: The Splendour of

Ceramics.

Portraits and Experimentation

The 1960s were a vital and sweeping decade for the visual arts in Argentina, most notable with the ebullience of the avant-garde centred at the famous Torcuato Di Tella Insti-tute, and it was also a marvellous time for ceramics. In 1960, the Marcelo de Ridder Prize for Young Argentine Ceramicists was awarded for the first time,12 and two years later the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires hosted the Annual V Exhibition of Ceramics and the First Interna-tional Exhibition of Contemporary Ceramics.13

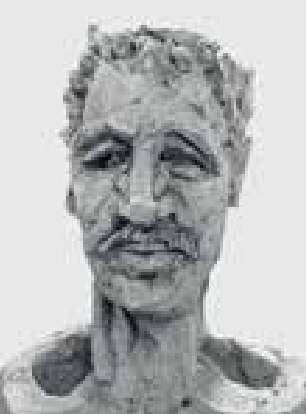

In 1962, Edelstein introduced the theme of the Moebius strip into his production – a theme of great interest to other artists, as well, among them the Brazilian Lygia Clark – with his sculpture Doble cinta de Moebius, Double Moebius Strip, made in both galvanised iron sheet metal and stain-less steel. It would be a theme he would revisit decades later because of his interest in mathematics and geometry. The strip is a three-dimensional figure that modifies the Euclidean way of representing space, questioning binary oppositions. Towards the end of this decade, Pablo used chamotte clay to create one of his most emblematic series of sculptures: busts portraying contemporary Argentine cultural personalities, plus a self-portrait. Among the materials available to him, the artist chose ceramics over others because, as he noted, it offered him the “best chances to do his work in a very personal way”.14 The series also enabled him to explore the transformative process of the portrait. To make the busts of these writers, sculptors, critics, painters and other personalities, he drew them in their homes, capturing them from different angles without posing them. His subjects were the luminaries of the city’s cultural scene: Antonio Berni, Romero Brest, Juan Car-los Castagnino, Cogorno, Manuel Mujica Lainez, Libero Badii, Soldi, Ricardo Garabito, among others. In the same interview, the artist noted: “I am interested in emphasis-ing the characteristics by observing their personality, their way of being, and later, in the studio, with what I committed to memory and with my sketches, I reconstruct.”15 The “reconstructions” were guided by working with the medium with great freedom, and achieving surprising textures from modelling the various shapes. The busts of the painters Horacio Butler and Leopoldo Presas were built up by the juxtaposition of coil shapes that generated accentuated voids and filled areas, light and shadow, lending the rendering an enigmatic view. With those of Vicente Forte and Soldi, for example, the prevailing shapes are flattened and irregular, joined in the manner of a collage, achieving a visual appearance akin to impressionism. Edelstein added incisions, overlaps and interlacing. The series of busts immortalises the subjects through their unique, human expressions, drawing on sculptural portraiture with its antecedents running through the history of art – in this instance, referencing the realistic depictions from the ancient Roman Republic – and, in turn, eternalising his creations. In the catalogue for his 1970 exhibition at the Rubbers Gallery in Buenos Aires, Pablo expressed this of his portraits: “As I search for the meaning of my own existence, ever more vividly stand out the qualities of those around me, of whom I want to capture not only their physical beings, but also their spirit, their character and their infinite destiny.”16

In 1971, Edelstein’s 10 piece sculpture Alegría de vivir (Joy of life) was awarded the Premio Adquisición (Acquisition Prize) at the Sculpture Exhibition organised by the Cinzano company and the province of Mendoza government. The 10 parts of the sculpture presented a new dimension to his small format dominated production, which was largely due to the constraints imposed by ceramic techniques. In order to learn more about glazes and engobe (white or coloured slips), Edelstein attended the workshop of the renowned ceramicist Mireya Baglietto during the first part of the decade. As Baglietto recalled: “I can say this about Pablo Edelstein, he was talented and had a gift with people, the sum of both resulted in ineffable outcomes. He was a sculptor who embraced ceramics as a material and incorporated it into his works without violating the essence of his sculptural work; from this perspective, he was a sculptor who made ceramics. I had the honour of having him as a student of the glazing courses for professionals that I gave a little over 50 years ago, his presence, without a doubt, elevated the group with his considered, friendly and intelligent comments.”17

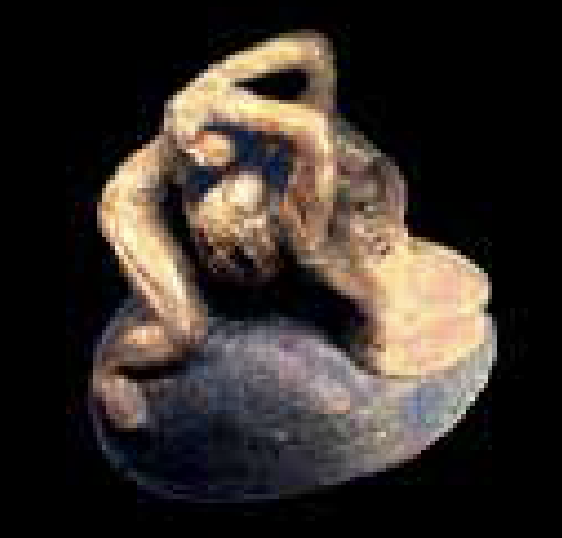

As his work progressed over time, his flexibility to address the same theme with different materials, techniques and compositional approaches became increasingly evident. In his terracotta Torso (Torso), Abrazo (Embrace) and Mujer al sol (Woman Sunbathing) sculptures, made between 1978 and 1979, and displayed at his Martha Zullo Gallery exhibition in 1980,18 each fragment of material becomes a geometric mass of curved lines articulating with another until achieving poignant expressiveness. Addressing this, the critic Guillermo Whitelow attentively noted that the works contained “a true latent primitivism, a true attempt at coarseness”.19 Torso, another terracotta, vividly reveals how matter, form, creative process and technique can coexist at equal levels of importance.

In Desnudo pensando en Modigliani (Nude after Modigli-ani) (1985), clay plates or segments are joined in an artic-ulated manner. The same technique is used in El sueño de Gustavo Courbet (Gustave Courbet’s Dream) (1987),18 but in this case glazing and the use of colour on the clay completely alter the texture and one’s perception of the material. The titles of both works invite the viewer to follow the artist’s gaze back through the history of European art to two of its giants, the supreme representative of Realism, with regard to Courbet, and, in Modigliani, a representa-tive of the avant-garde identified with portraiture and the human figure.

“I like to experiment. With marble, for example, I have not worked from a single mass but by assembling, which in itself is a form of collage,” Edelstein explained.20 Far removed from Renaissance orthodoxy, in his hands the marble was masterfully related to collage, the composi-tional form born of the avant-garde, giving rise to pieces such as Toro de marmol (Bull in Marble, 1970).

In turn, in Calzándose (Putting on Shoes), a glazed ceramic sculpture from 1987, the position of the female figure leads back to 1948’s El labrador and allows those flattened strips to project their later development in the Moebius strip. In 1987, the artist incorporated computer science into his cre-ative process, using digital photography to examine new shapes, colours and light contrasts from different angles

1990-2000, A Change of Century, Materials and Scale

Edelstein received the Certificate of Merit in Ceramics in 1992, awarded by the Konex Foundation, an important hon-our distinguishing him as a ceramicist and as a torchbearer of the discipline during his more than 30 years of teaching.

Towards the end of his career, Pablo held numerous indi-vidual exhibitions in Argentina and Uruguay, finishing with his retrospective exhibition at the Recoleta Cultural Centre in 2007,21 which was curated by Raúl Santana.22 For this occasion, more than 30 works were presented in sheet met-al, bronze and stainless steel, together with a series of ink drawings, all representing recent works. Notably, his works became larger during this period, likely a result of his use of sheet metal. From small ceramics, he went on to shape this material to encompass greater spaces, for which he had to resort to industrial facilities.

Edelstein modelled sheet metal as he modelled clay: where he managed to rescue the simplicity of clay and its rudimentary texture, with metal he sought to enhance the effect produced by folding, pleating or coiling it, along with how light played on it. The artist never wavered from his investigation of “the tactile quality of the material”. With the metal sheets and their luminosity enhanced by the lustrous finish of the steel, Edelstein achieved a weightlessness that belied the nature of the material.

The concept for a work begins with sketches or, at times, more detailed drawings other times, the premise might be based on paintings, or collages, or small cardboard models. As Pablo so frequently insisted, the process was the most enjoyable part of creating, as is evident in these pieces.

Without completely abandoning the figurative in these years, the artist started from anthropomorphic motifs, which he then subjected to a process of abstraction, achieving a linear synthesis. In this way, clover leafs, origami and Moebius strips arise from internal and external spaces as undulating and angular forms.

He continued creating his ceramic sculptures alongside his metal productions. The figurines, usually women or animals, were formed by clay plates, or patties, that are articulated, a technique replicated in his collages of that time. “Having worked with clay, marble, cast bronze, wax, plaster, cement and polystyrene foam for many years, the change of material has allowed me to explore new possibilities of structures by giving up volume and assigning prominence to curved surfaces”,23 Edelstein explained.

Pablo continued working until the end. In his last works, almost exclusively collages, he returned to working on his homage to Italian Neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova, one of his favourite artists, who he felt was truly able to capture the sensuality of the human body in marble.24 The collage triptych – perhaps closer to a sketch for a planned relief – synthesises the themes, forms and compositions that were evident in his work throughout his extensive career.

Without a doubt, Pablo Edelstein’s artistic universe, com-bined with his warmth and empathy, reminds us, in this 21st century’s convulsed and uncertain third decade, that art is a horizon of encounter, beauty and reliable knowledge waiting for those who move towards it with work and dedication.

References

1 Interview with Pablo Edelstein by his daughter Verónica Edelstein, Buenos Aires, 31 July 2002.

2 Jorge Larco. Watercolourist, illustrator and decorator (Buenos Aires, 1897-1967). Instructor at the Escuelas Nacionales de Bellas Artes.

3 Financed by famous Spanish publisher Gonzalo Losada, who lived in exile in Argentina after escaping the Franco regime.

4 As Edelstein recalled, “they were a group of friends that had, for a long time, expressed a mutual esteem, though they espoused different

aesthetic philosophies”.

5 Villaverde, Vilma. Arte cerámico en Argentina. Un panorama del siglo XX. Buenos Aires, Editorial Maipue, 2014, p.65.

6 Villaverde, Vilma. Arte cerámico en Argentina. Un panorama del siglo XX. Buenos Aires, Editorial Maipue, 2014, p.28.

7 Letter from Pablo Edelstein to Teresita Rasini Fontana, not dated, circa 1987.

8 At this time, Italy was the chosen destination for several artists, such as Emilio Pettorutti, Antonio Berni, Santiago Cogorno, and others.

9 Letter from Lucio Fontana to Pablo Edelstein, Milan, 9 October 1949.

10 As María Martha Pichel, one of Edelstein’s many students, recounted “the way of seeing was the greatest legacy that Pablo left us”, recalling that his classes were a kind of “laboratory”. “The greatest pleasure an artist can experience is enjoying the creative process”, Pablo professed throughout his entire career and shared generously with his students.

11 The CAAC ( Argentine Centre for Ceramic Art) was founded in 1958. Among its founding partners were Aída Carballo, Ana Mercedes

Burnichón, Roberto Obarrio, José María Lanús and Marciano Longarini.

12 Villaverde, Vilma. Arte cerámico en Argentina. Un panorama del siglo XX. Buenos Aires, Editorial Maipue, 2014, p.161.

13 De Carli, Ernesto. Crónica del Centro Argentino de Arte Cerámico, 1958-1998.

14 Padilla, Alejandra. “Entrevista al artista plástico Pablo Edelstein”. Monograph. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2007.

15 Ibídem.

16 Exhibition catalogue, Pablo Edelstein. Esculturas, Buenos Aires, Galería Rubbers, 15 to 29 April 1970.

17 Mireya Baglietto interview, Buenos Aires, June 2001.

18 Pablo Edelstein. Pinturas y terracotas, (cat. exp.). Galería Martha Zullo, Buenos Aires, 18 September to 9 October 1980.

19 40 Escultores Argentinos, Ediciones Actualidad en el Arte, Buenos Aires, 1988. Page 269.

20 Padilla, Alejandra. “Entrevista al artista plástico Pablo Edelstein”. Monograph. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2007.

21 Pablo Edelstein. Esculturas en chapa metálica (exhibition catalogue). Centro Cultural Recoleta, Buenos Aires. 23 February to 18 March 2007.

22 Raúl Santana, who recently passed away, was an important figure in Argentina’s art world . He was an art critic, writer and curator, as well as director of the Museo de Arte Moderno and the Palais de Glace.

23 Pablo Edelstein, the artist’s archives.

24 The Italian artist, an exemplar of Neoclassicism, was a master of capturing the sensuality of the human body in his marbles. In 1989 Pablo created his Amor y psiquis sculpture, a direct allusion to one of Canova’s best known works.