Life

Pablo Edelstein opens the door of his studio on Laprida 2050, between Gutiérrez and Melo streets, and walks into his world. Soon the model and the students will arrive, a blank canvas awaits. Crossing the entryway, he continues down the passageway, greets the three florists to whom he rents a space at the front, and walks energetically to his studio space on the far left.

The courtyard houses a jungle of begonias, small rubber trees, ficus, bromeliads, spider plants, philodendrons, palms and cat’s claws, which he devotedly cares for. The bathroom is always splashed with colours. His ceramics workshop is upstairs, filled with figurines who each day watch him work, planted, as if he himself were a tree. A large statue of Hipólito Yrigoyen is at the rear – modelled for a competition – obscuring the huge kiln, because ceramics is an art of fire and baking, linking the work with those of bread, pastry, agriculture, the cultivation of the soil, which also serve to identify it.

On the radio, the journalist Hugo Guerrero Marthineitz is speaking in his deep distinctive voice. Edelstein’s face is always filled with excitement and joy, and within these walls, no one has ever seen him wear a taciturn or conflicted expression. Art is his adventure, his pleasure.

Whether by mandate or genetic predisposition, he studied agriculture, but his passion will be the visual arts, a maternal legacy. He never stopped teaching, studying and, above all else, creating art. The two worlds intersect in his life and in his work, as he will dedicate his days to both raising cattle and modelling bulls in ceramic or clay, drawing women in colour, and elevating metal forms into space.

Edelstein was born in Switzerland in 1917 and died in Buenos Aires in 2010. He devoted himself to agricultural work for several years, later settling permanently in the city of Buenos Aires in 1944, where he began his vast artistic and educational activity. He was already familiar with many of the world’s museums, attended art classes as a child, and had a cultural background that encompassed music and literature. He was also quite athletic, winning awards in fencing, skiing, horse riding and swimming.

Biographical information chronicles his formal art education as beginning with classes in Buenos Aires with the painters Jorge Larco and Raúl Soldi, and also the sculptor Lucio Fontana, with whom he would maintain a lifelong friendship. Starting in 1946, his curriculum vitae expanded year after year through both national and international exhibitions. He worked in the upper echelons of the discipline that was so dear to him, even serving as an adviser to the National Ministry of Culture during democratic administrations.

Many of his works are in the possession of important private collectors and museums in Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Spain, Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom and the United States. Edelstein was a generous and dynamic teacher for 37 years, working side by side with his students. He also conveyed his vision and his techniques in Argentina’s national schools of Fine Arts.

His career would bestow him with joyous rewards, such as the Third Sculpture Prize at the Salón de Mar del Plata, the Gold Medal at the Salón de la Sociedad Hebraica Argentina, the Gold Medal at the Monument to Hipólito Yrigoyen Competition, and the Konex Award for Ceramics. Monumental pieces and murals leave their mark in public spaces such as the La Alborada (Daybreak) fountain sculpture that he donated and now adorns the Fundación Favaloro courtyard; the bust of Juan XXIII that stands in a plaza in the province of Corrientes or Alegría de vivir (Joy of Life,1971), the marvellous grape harvest-themed sculptural grouping that adorns the Fader Museum courtyard in the province of Mendoza. In 2007, the Asociación Argentina de Artistas Escultores inducted Edelstein as a member of its Court of Honour.

But no accolade would give him as much pleasure as sinking his hands into a mass of cold clay or sketching a woman’s nude body on a blank sheet of paper. He mastered ceramic sculpture, painting, engraving and drawing, venturing into collage, and multimedia happenings. A lifelong obsession with the human figure led to him refining and synthesizing it until it had become angular. Towards the end, he will find himself enthralled by the Moebius Strip and the desire to capture the idea of infinity in a sheet of metal.

Origins

Hoppe, hoppe Reiter,

wenn er fällt dann schreit er.

Fällt er in den Graben,

dann fressen ihn die Raben.

Fällt er in die Hecken,

tut er sich erschrecken.

Fällt er in den Sumpf,

dann macht der Reiter plumps!

At 85 years old, Pablo Edelstein is in the living room of his house surrounded by loved ones. His lifelong wife leans on the back of his chair, his daughter gazes at him with rapt attention, and his grandson films him. Pablo again sings the German children’s song he sang along with his maternal grandfather as he bounced atop his knee as a young child, one that remains a family tradition: Hop, hop, rider / When he falls, he will cry / If he falls into the ditch / Then the crows will eat him/ If he falls into the hedge/ Are you scared? / If he falls into the mud / The rider goes Plop! He has sung it thousands of times, as a boy, as a father and as a grandfather, each time bringing him the same joy.

It must have been a scene he experienced with his father when he was being taught to ride while still wearing knee pants – a scene he would relive with his own son. Riding is a serious endeavour in the Edelstein lineage. That day, Pablo was galloping with his six-year-old son, each on a spirited, pure-bred chestnut horse. As they gathered speed, his son lost control and fell. He didn’t want to climb back on, but Pablo encouraged his son not to be afraid. And, so, with his father’s reassuring gaze and his unconditional support, the boy again mounted the horse and became a rider. Over time Edelstein would himself become quite adept at encouraging and nurturing.

A very old photograph, perhaps hand-painted, shows him as a boy with chubby cheeks, and blond hair cascading over his blue eyes. There is the cuteness of short trousers, high socks and little shoes, as well as the apron worn back then so as not to soil the fine clothes, the embroidered collars, the corduroy onesies and the starched, pristine new shirts.

What inspires a boy who barely knows how to count or spell but has already travelled to a good part of the world? Without a doubt, art never ceased to thrill Pablo Edelstein, son of an enlightened Europe, champion swordsman and horseman, lover of music and literature, yet, at the same time, a baqueano, completely at home in the great pampa, a loving father and dedicated teacher. A thoroughly passionate artist. An encyclopaedically knowledgeable dandy or a romantic hero.

In 2002, he would recount the details of his childhood to his daughter Verónica. He was born on August 14th, 1917, in St. Moritz in the Hotel Suvretta Haus, which opened in 1912 in the heart of the Alps, overlooking Champfèr and Lake Silvaplana from its location on the Chasellas plateau.

His sisters, too, were born in Switzerland; Carola in 1915 and Beatriz in 1920. “My parents lived there because the First World War was going on”, Pablo told his daughter. It was an exclusive tourist resort located in the Engadine Valley, which 10 years later would be the Olympic Village, its frozen lake hosting polo, cricket and horse racing on ice, as well as five world ski competitions. A progressive mountain own that was the first to be wired for electricity, and have the first ski school in the country.

Sigmund Edelstein, his father, was a prosperous Austrian, a grain merchant and agricultural producer. At 40, after 20 years working from sunrise to sunset, Sigi had already retired from business. During the course of the first world war, at the insistence of his partners, the Weil brothers, he rejoined the firm. He moved the offices from Antwerp to London to evade the German occupation, and later founded the Rotterdam office in the Netherlands. After resuming his business activity, he would not retire again until he was 70 years old.

Pablo’s mother Lisbeth was two decades younger than Sigi. She was 20 years old when they married in 1912, and died at 33 of lymph node cancer. Although Sigi never remarried, his dedication to his children and his work kept him spritely and active.

Pablo grew up between Switzerland and the Netherlands. He spoke German with his parents, but his first language was French, as his nanny was from Lausanne. “We spent spring and autumn in the Netherlands, and the rest of the year in Switzerland, in St. Moritz or Zurich. But when my mother passed away, my father needed to return to Argentina to restructure the firm after two principal directors resigned. In 1924 I came to Argentina for the first time. My father had arrived at the end of the 19th century and later became a naturalised citizen, but, though my sisters and I were born in Switzerland and were registered at the consulate in Geneva, upon turning 17 we opted for Argentine citizenship as the children of a naturalised citizen, because Switzerland’s Lex Sanguinae law only recognised those of Swiss ancestry as citizens”, Pablo explained.

In those early years they toured the mountains in Córdoba, as well as visiting Rosario, Mar del Plata, La Plata and other places. “My father travelled those places far from Buenos Aires on horseback or by stagecoach. We returned to Europe by sea almost every year as he would go to the Netherlands for business, and we would go to various places on the southern coast of France to visit both our father’s and mother’s families. Later, in 1930, my father retired for the second time, at the start of the Great Depression. The fall in prices of raw materials and agricultural products made the business of grain export from Argentina nearly unsustainable, leading him to decide to liquidate the firm. Together, we first travelled to Switzerland, where my father wanted to buy a property on Lake Zurich, but he finally settled on Vienna, his hometown”, recalled Pablo.

While still in Argentina as a child, Edelstein attended primary school at the Goethe-Schule for a while, a Germany-sponsored institution, later attending secondary school in Switzerland and, from 1930 to 1935, at the Theresianische Akademie in Vienna, which was founded by Empress Maria Theresia. From there, he toured Europe on school holidays, visiting such places as Florence, Sicily, Rome, Venice, and the Alps, and in summer, the Dolomites, French castles and the south, England and Scotland. It was at this time when, as a boy, he was initiated into the world of art, having already visited some of the most important museums in the world.

“I felt very awakened to nature’s beauty, having been raised in places that so displayed the changes and transformations that occur within them when the seasons change. This has formed part of my work since my first efforts”, says Edelstein. Before her marriage, his mother studied Art History in Germany at Mainz and Frankfurt, thereby bequeathing him a very rich library. “My birth coincided with the rise of Dadaism at the famous cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, where my mother met many painters and sculptors of the time”, he said. Pablo proudly carries the name she chose for him as if it had been a premonition or part of a grand design. A great number of artists that his mother admired shared the name: Cézanne, Gauguin, Rubens, Veronese and Picasso.

His memories of her are as being young and beautiful. “All this coincidence must have created in me a strong desire to study art; especially when living in Vienna, with its rich collections in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, the Museum of Art History, where the best of Bosch, Brueghel, Dürer, Rubens, Rembrandt and the Flemish schools can be found.”

But his father did not share his vision, opposing his son’s plans of pursuing a career that did not guarantee a solid financial grounding. “One doesn’t live on art, but agriculture will always feed you”, he told him. An artist, he thought, could hardly live off his work. He was somewhat correct, as Edelstein never viewed his work as a commodity, nor did he dedicate time and energy to establish it in the market. While he did enjoy some success, he did not actively seek it.

“As the family had interests in grazing land in Argentina, he suggested that I study agriculture. I did so, but I never gave up on my desire to be a painter. As a student at that time, I took full advantage of lessons I received from a secondary school drawing teacher who came to our home to instruct me in art history and oil painting, charcoal drawing and watercolour techniques. What I learned was later reinforced by visiting many museums around the world. But I remember that my mother took me to museums in Amsterdam, The Hague, Haarlem and Delft during my childhood in the Netherlands, much the same as other children are taken to the zoo. Later, I also attended the Montessori school in the Netherlands, where they greatly stimulated my imagination and arts activity; so collage, drawing, and all that, came into my life at the age of five or six as an everyday thing”, he explained to his daughter.

After secondary school, he began university studies in agriculture in Vienna, continuing them later in Great Britain. Back then, he travelled to Canterbury in his spare time to take painting and sculpture classes. He also interned at a stud farm in Scotland for two years, further helping him perfect his English.

He was visiting Argentina to spend time on the family properties when the Second World War began so, as he was unable to return to Europe to complete his university degree, he ventured to the United States to take graduate courses in Ranch Management and Agriculture, at the University of Iowa and University of California. He travelled 70,000 kilometres in that country to visit experimental farms, and the friendships forged there lasted a lifetime.

He devoted himself to rural activities1 in the southern part of Santa Fe province and in the province of Buenos Aires during the early 1940s – both the time and the regions holding a place in his memory. “It was there I learned to look at the land more dynamically, and the ways nature changes with the passing of the seasons. When I was developing my skills as a ceramicist, I knew that, with such variables as moisture, dryness or temperature, earth has various consistencies, other facets, which I attempted to convey in my works. But because of family reasons and differences, I finally decided to leave behind my farming and ranching activities in 1944 when I married my wife – very much a city person – and take up learning visual arts seriously.” It was from those years in the campo he adopted the customs of drinking mate (tea) and living surrounded by greenery, even if it meant just taking care of potted plants and planter boxes – something else he was quite good at.

The artist takes form

Meeting Mercedes Rodríguez, Nena, changed his life. He was running a ranch in Necochea and went to dinner with friends one night at the Hotel Bristol in Mar del Plata. Nena went there the same night with one of her three sisters and her brother-in-law, who Pablo knew. Pablo was 27, quite the good-looking dandy, and a gentleman. Just recently, he had been driving European roads in a dual carburetor convertible with luggage made of the same leather as the seats. But that night, when a famous orchestra began playing, Pablo asked Nena to dance. They didn’t return to the table until the festivities ended some two hours later. He had had many loves, but when he held Nena’s waist he knew she was the one.

But Pablo’s father objected. He wanted a European woman to continue the lineage, but there was little he could do. The courtship, replete with letters and delivered flowers, lasted just six months. “The third time I saw her, two months after we met, I proposed to her”, said Pablo. She was a Spanish and physical education teacher of Asturian descent, and who, with Pablo, loved to dance. They stayed in a suite at the Plaza Hotel Buenos Aires for the first few days after they married. Together for six decades, they had two children and, later, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. They danced throughout their life together. At 87, Mercedes passed away just a few years before Pablo.

Work, production and creation. Pablo continued to enjoy everything the world offered, but he never lost his humility. He didn’t share his father’s elitism. He wasn’t driven by success but, rather, by doing. As he repeatedly said, like a mantra, throughout his life: “The creative process is an essential theme for me. I was always more interested in the process than the final work. My work starts with sketches, from earlier studies, which I believe to be part of the final work.”

As he did not obtain a university degree in Argentina, he wasn’t allowed to enroll in the country’s official art schools. He did, however, attend Jorge Larco’s studio on Tres Sargentos street for two years. Larco taught him watercolour techniques, of which he was an outstanding teacher, and enjoyed chatting with this extraordinary connoisseur of culture.

The Altamira Escuela Libre de Bellas Artes art school opened in 1946, and Pablo was one of the first to enroll. It had always been his desire to study sculpture, as his mother had done. There, among other subjects, he studied sculpture and ceramics with Lucio Fontana, the forerunner of the country’s ceramic sculpture movement. He and Pablo became bonded by a deep friendship. Founded by Gonzalo Losada, the Altamira School also enabled him to take classes with Raúl Soldi, Laerte Baldini for engraving, and aesthetics and art history taught by Jorge Romero Brest, later of the legendary Di Tella Institute. “When I was 27, I poured every ounce of my passion and energy into expressing myself through this medium”, Edelstein told his daughter.

It was during this time he formed a friendship with Santiago Cogorno, whom he met through Soldi. “Their mothers were sisters who had come from Italy. Santiago exhibited for the first time in 1946 in Altamira. His temperament, his courage and his originality impressed me deeply, his friendship made me feel as if we were brothers […]. When he was speaking seriously about art, he showed the grounding and conviction of a man fully aware of his responsibility and the need for artistic expression”, Pablo said.

Fontana worked in small ceramic establishments in Italy’s Liguria and also at the Cattaneo factory in Buenos Aires, creating a number of unique terracotta ceramics pieces bearing his style and signature. It was he who introduced Edelstein to the secrets of glazes and kilns. When Pablo returned to Italy, he met Jorge Oteiza, a former student of the influential Argentine ceramicist Fernando Arranz. Among his other teachers were Tulio Mazzetti and Agenor Fabbri, Italian sculptors who worked alongside established artisans in Liguria. Later, he studied glazes and slips with Mireya Baglietto.

After the Altamira School, Edelstein and Fontana shared a studio located in a building that had belonged to the Bullrich family, and where Emilio Pettoruti and María Juana Heras Velasco also had a studio. The former mansion is also notable because the writer Manuel Mujica Lainez used it as a setting for a novel, while a well-known dancer from the Teatro Colón also had a dance studio there.

Fontana invited Pablo and other artists to sign the Manifiesto Blanco, White Manifesto, which held in part that, “Matter, colour and sound in motion are the phenomena whose simultaneous development the new art integrates”. But Pablo thought that aligning himself to philosophies of others would compromise his own artistic integrity and declined to sign it. He respectfully explained to Fontana that he was there to learn, he did not fully understand the text, and that he did not feel mature enough to support it. Pablo continued his development as a ceramicist.

The long correspondence between the two artists allowed them to share that which concerned them or their moments of joy, exchange favours (Edelstein took care of some official paperwork for Fontana, or kept track of his works in the country, and Fontana, in turn, would send him specific Hanovia brand pigments). Handwritten by Fontana, typed by Edelstein, the words came and went in letters that crossed the ocean, serving to maintain a friendship that endured decades. Even after Fontana’s death, Edelstein continued the correspondence with Fontana’s widow, Teresita.

Edelstein was extremely active and prolific even at the start of his career. He began exhibiting in national and international art shows in 1946, earning him numerous awards and distinctions, continuing his participation each year in group shows and competitions. He would frequently be found at colleagues’ exhibition openings, as he viewed several exhibitions per week. In 1947, he held his first solo exhibition at the Müller Gallery, later, and throughout his life, his work was shown at the Witcomb, Rubbers, The Art Gallery, Martha Zullo, and Isabel Anchorena galleries, along with several others in Buenos Aires, other Argentine cities, Brazil, Germany, Italy, and Uruguay.

Being an artist was a full-time job for Edelstein. His great-niece Alejandra Padilla, also an artist, remembered him as always working on a drawing. During summers spent with the family at the beach, Pablo always had a pad and a small art box with oil pastels so he could draw by the sea or render a portrait. “He was a very committed artist, always producing a great deal of work”, she recalled.

Work

It is no coincidence that Edelstein was a gifted athlete and at the same time a sculptor who derived great pleasure in modelling the human form in movement. For him, mastery of the body, the muscles working in harmony and, at the same time, the will, the power of the mind over the body, were fascinating, themes he also found in dance.

It’s a pleasure to see his hands moulding the material in an old video. They are large and gnarled, much like the figurines he creates. They move quickly in short, repeated movements that eagerly strive to capture the shape he has visualised. There is an intuitiveness in those determined and emphatic fingers.

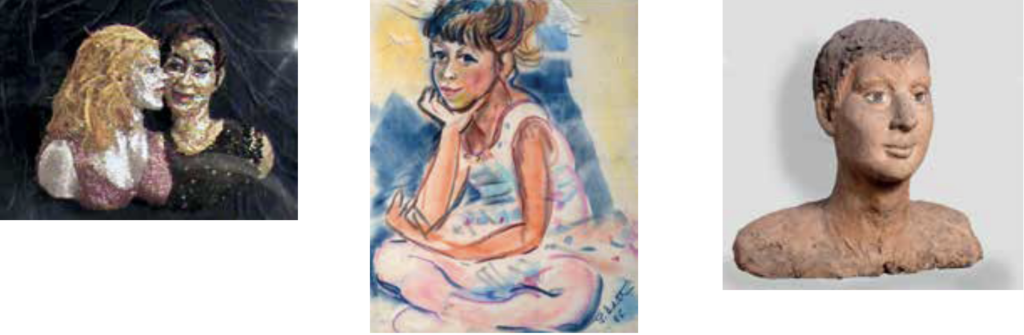

There is a notable element of romanticism in his early works, the development of the human figure from the drawing to three dimensions through constant sculpting in plaster, clay, wire and ceramics; his oeuvre containing the human figure, eroticism, bullfighting, floral subjects, landscapes, portraits and still lifes, along with experimental and geometric themes and abstraction.

Sculpture, painting, ceramics, drawing or performance. Edelstein doesn’t value one discipline over another: what matters to him is the process. He works on his projects with a calm energy, swiftly but never brusquely. Even while involved with several things at once, he maintains his serenity. He also remains attuned to the times by reading, questioning others, travelling and visiting exhibitions. Fontana, in his letters, keeps him abreast of what is happening at the Venice Biennales. He is a man of adventure, launched into the future, without prejudice or fear. Something of that is evident in his love for storms. In the face of torrential rain, lightning and thunder, Edelstein moves towards the windows or settles himself on a chair on a terrace and prepares to enjoy it all. Perhaps it reminds him of the adrenaline rush of climbing, of the time he reached the summit of Mount Fitz Roy. “Lleva quien deja y vive el que ha vivido” (Takes the one who leaves and lives he who has lived) is a verse by Antonio Machado that Edelstein was fond of repeating.

He regularly entered competitions for the challenge. He participated in the Watercolourists and Engravers National Show in Buenos Aires in 1947. That same year he exhibited a painting called El viento de blanco (The White Wind) at the Müller Gallery. Years later, his friend Santiago Cogorno would tell him that he anticipated the Informalism movement with that painting.

Thirty years later, at the Martha Zullo Gallery, the critic Sigwart Blum recalled that first exhibition and, citing the few individual shows Edelstein had had, suggested it was time for a retrospective. He defined him as an artist reluctant to gain fame: “For this jovially spirited and enthusiastic artist, finding solutions for formal and compositional challenges has become his primary objective.” J. Linares wrote about that same exhibition and, dazzled by Edelstein’s erotic drawings, described him as a mature artist who knew how to use his media skillfully, saying, “Edelstein is an artist of dynamic and passionate expression”.

He worked standing before a high table in his pottery studio, rolling out several clay coils with which he fashioned the subsurface features of a figurine, gradually forming them together. Above that, he would use smooth clay patties, sometimes finishing the work so only the exterior can be viewed, other times leaving the layers in evidence. Before starting a piece, he would quickly fashion a few clay models in order to examine the movement. He would occasionally fire these figurines, creating little treasures that he left lying around or gave away as gifts. Glazed pieces crafted by his children and grandchildren were often also found in his studio. His studio was a space with open doors.

He started from drawings that he often made in his live model classes, where he worked alongside his students. The sketches were done quickly, spontaneously and uncorrected, using one sheet after another. He was particularly keen on Pelikan inks, which he used by dipping the brush straight into the bottle. He also worked in watercolours and oil pastels. His week was divided into days with a live model and others dedicated to ceramics. His sculptures based on the sketches he made on those other days. Papers filled with notes were an integral part of the process of his sculptures, piled high on an untidy table, an irreducible mountain. From time to time he gave classes on theory that everyone enjoyed and that were sprinkled with extracts from literature and music. He insisted on searching for the axis, the bone structure.

While in his studio, he moved between working with paper to ceramics with the same pleasure. Everything made him happy in his workspace. “Nowadays there isn’t any solitude, no sense of proportion, no silence. The air is permeated with noises, crossed by parades. This studio is a place of tranquillity. It might seem like I’m exaggerating when comparing it to a cathedral, but sometimes I feel that the atmosphere is a bit that way. I really enjoy sharing this space with my students. But I also enjoy it when I’m alone”, he said in a 1993 interview for the magazine Cerámica, on which he was featured on the cover, surrounded by his busts and figurines, as a conqueror of space and time.

“Ceramics have the demureness to move one with simplicity”, he was quoted, going on to explain his reluctance to engage in mega-exhibitions and big shows. “Ceramics reveal the man. The sacred, the mundane, the commercial. The amphorae not only transported oil and grains, they also carried stories with them […]. It is difficult for a form to be imbued with permanence in these times of video clips.” He soon discovered clay as the definitive element for his work, rather than using it only for the intermediate stages of his sculptures, no longer abandoning it as a means of expression and experimenting.

In that same interview, he talked about the experimental condition of his work, the persistent search: “It forces me to rethink the process, over and over again, always anew, with the purpose and secret desire of deepening and improving the means of expression.” He always starts with life drawings, with anthropomorphic motifs especially portraits but also animals or plants. Afterwards, he subjects these spontaneous sketches to a process of abstraction so that they work well with the plastic and structural requirements dictated by the ceramic material it self. “In this process, intuitive impulses and conceptual thinking intervene simultaneously, or, at least, that’s how it seems to me, often resulting in surprising or unexpected outcomes.”

For his pictorial work he used acrylic, pastel, oil and watercolour almost exclusively for many years, which he applied with quick rhythmic brushstrokes, little material and forceful colours. A new change of concept and expressiveness occurred in the later years of his life, returning to collage and relief, techniques that he developed through the use of synthetic fabrics, with metallic elements and a multiplicity of colours, as well as coloured paper and metallic sheets, with paillette applications, sparkling metal sheets, feathers and rhinestones.

He also ventured into the Happening in the mid-1960s. In this case, a participatory exhibition by Edelstein at the Witcomb Gallery for the benefit of the Confederation for the Recovery of the Cardiac Incapacitated (CORDIC), that included photomontages by Pablo Suárez and music by Néstor Astarita, and ended in a pitched battle of styrene foam. Before that, the public was invited to create their own sculptures at one of the first participatory exhibitions in living memory. Thirty sheets of foam were laid out, along with pistols, after which the foam was modelled, and it turned out to be quite an event that was enjoyed by all there.

The antics of the end of that day were wonderfully captured in a story published in the magazine Gente titled “Not Advisable for Cardiac Patients”, in its November 1966 edition: “It was 6:30 p.m. The crowd entered the ‘ship’. Edelstein, resplendent in his blue costume armour with a newly fashioned styrene foam helmet, was smiling. Youthful admirers of Marta Minujín walked among serious ladies and gentlemen. Suddenly, the room went dark. Drums roared as if a hundred rockets had been fired at once. In the dark, women’s shrieks were drowned out by an even greater voice, one of those yells that even Burroughs’s Tarzan would have envied. Someone had thrown a piece of styrene foam that hit someone’s head and… well. Just as the Battle of Pozo de Vargas was fought to the rhythm of zamba, this ‘battle’ was accompanied by jazz rhythms […]. The fight went on for 15 minutes. Two boys discovered two bags of crushed styrene foam on the top floor of the ‘spaceship’ and dumped them on the people below, as if it were a carnival.”

Edelstein’s parties in Punta del Este were legendary. He once hired the Shakers2, a fashionable band at the time, and received guests in overalls and a wig, and painted live to the music’s rhythm. His wonderful canapé creations, his warmth as a host, and his skill at dancing Viennese waltzes are also remembered.

Edelstein used clay, marble, bronze casting, wax, plaster, cement, and polystyrene foam to create spatial shapes. He even made soap sculptures. Many years later, at the age of 80, he began using aluminium for his works, folding the sheet metal to achieve greater dimensions. Always wishing to innovate and not repeat himself, he began incorporating computing into his production process in 1987, using digital photography to examine new shapes, colours, and the contrast between light and shadow from different angles.

He also alternated his use of materials in his pursuit for new depictions. “An object moulded in ceramics or carved in marble or assembled with slabs of stone, or also when working with styrene foam or making a collage with feathers, velvet, paper, metallics… each of the materials leads you towards a different image, much the same as the techniques employed will alter the results”, he explained.

He challenged the limits imposed by a material by experimenting. He worked with marble as one would a collage, assembling pieces. He tried glazes on ceramics that he could never replicate. He worked with lowering firing temperatures, using both harder and softer glass glazes. Instead of using lost wax for his bronzes, he used lost styrene foam, which vaporised, leaving space for the molten bronze.

What Edelstein loved most was ceramics, modelling figures in a material that is little more than earth, allocating the medium a special space in his studio and a marble tabletop that managed to withstand his energy. He used clay in slabs, tubes, joining, and strips of overlapping coils to model on a hollow base. His favourite type was chamotte, a coarser, calcined clay that is crushed or ground, to which he added clays with more elastic properties to give it strength and also reduce shrinkage.

He created many of his statues or busts of contemporaries with the material, including writers, sculptors, critics, and painters. Again, he started from drawings, in which he sought to define aspects of the subjects’ characters and personalities. Relying on memory as well as the sketches, he reproduced their faces and gestures. “It is very interesting to see the transformation that occurs between recollection and outcome”, he said. He sought to recreate their world, the poetic intensity of the model – or of their emotional being.

He didn’t always glaze his ceramics, as he explained in one interview: “I look for the tactile and visual quality of terracotta, the coloured earths and the slip. I vary the effect on the glazes by alternately resorting to oxidising and reducing atmospheres during firing. I use various frits [ground glass] for creating different types of fusion in the same piece to obtain shiny and matte surfaces simultaneously.” His technique is the result of endless experience and testing. He was always after originality, coherence, structure, rhythm, colour, tactile and visual values, and good firings and good maturation of glazes. “The Argentine ceramicist continues to be a rudimentary, wasteful craftsman, with remarkable creative and expressive capacity”, he asserted.

“Three dimensionality accentuates the contour and the contour accentuates the three dimensionality”, Edelstein said. “It is the polish, the roughness, the contrast that gives three-dimensionality to the sculpture. Space is modelled by the form, and they complement each other. On the other hand, in the two-dimensional plane, for example, and in drawing especially, the rhythms of the contour are fundamental for an image to make sense. It is at that limit of space where they complement each other like negative with positive, the filling with the void.”

In 1952, in search of an activity that was both ceramic-based and profitable, Pablo founded a company for the manufacture of mosaic tiles, in which he applied the technique of single firing for bisque and glaze. This enterprise allowed him to continue experimenting with ceramics. As Pablo described, it was a very interesting technical experience but financially disastrous due to the recession and inflation at the time, as well as the difficulties in marketing. Ten years later, in 1962, the factory closed its doors, proving to be more of a headache than a lucrative endeavour.

In truth, the pursuit of prosperity was never terribly important to him, partly because he had benefited from inheritance and partly because he was not interested. “The spirit does not exist without matter”, he stated in an interview. “The spirit becomes visible in the traces it leaves on matter. For this reason, the artist feels the need to leave a testimony of what happens to him, excites him or it saddens him, and that testimony has the sense of leaving an imprint […]. In this sense, it becomes a necessity. On the other hand, amassing material wealth has no other meaning than providing the material needs of existence, which are, by the way, some of the needs but not all.”

In the Belgrano neighbourhood of Buenos Aires, the building on the corner of José Hernández and Arribeños streets, his work La Cascada, The Waterfall, serves as a testimony to that time – cascading the full 10 floors of the façade and made entirely from his factory’s mosaic tiles.

Edelstein was both a founding and honorary member of the Argentine Centre for Ceramic Art. Current and active artists gathered there to hold exhibitions and convene forums and juries. In the group’s minutes, Aída Carballo and Leo Tavella, among others, expressed their desire to create a centre that would bring together ceramicists and that would be represented in Argentina’s Federation of Visual Arts.

The group’s future is detailed in the Crónica del Centro Argentino de Arte Cerámico 1958-1998, Chronicle of the Argentine Centre of Ceramic Art 1958-1998, authored by Ernesto De Carli et al. The goal was achieved in 1976 when the group met for the first time to represent Ceramic Arts at the Palais de Glace’s National Hall of Visual Arts.

The members were multidisciplinary artists, many arriving at ceramics from other branches of fine art. “This status removed the bonds that tethered ceramics to traditionalist art, as this generation of artists proposed to incorporate in their work the new concepts of the time: informalism, the deconstruction of the human figure, framing and reframing in sculpture, the use of colour not as a patina but incorporated as a material in itself, the experimental mixture of different materials melted or fused into the clay (such as iron, crockery, glass, porcelain, etc.), an expressionist language in the construction of form and use of colour”, wrote María Gabriela Luna in the article “Cerámica y arte contemporáneo: Una dura trayectoria en proceso de consagración” (Ceramics and Contemporary Art: A Difficult Path through the Process of Recognition).

In 2006, when the International Conference on Contemporary Ceramics paid tribute to him as the guest of honour, the artist prepared a small retrospective of five works covering his career from 1955 to 1987. The works were figurative: a bull, a figurine of a colleague (the Argentine-Spanish drawing artist, painter, engraver and writer Luis Seoane), two female nudes, and an erotic scene. They are all assembled hollow pieces, without internal support from anything other than ceramic. The assembly refers to the collage technique. In the first two, the chamotte finish accentuates the search for constructivist rhythms and orthogonal directions. In the latter, the glaze accentuates the curvaceous trend. Galataia, from 1983, finished with lead glaze, reflects firing in an oxidation atmosphere, plenty of oxygen for the kiln. América, 1984, and El sueño de Courbet (Courbet’s Dream), 1984, are coated with glazes that metallize in a reduction atmosphere, where the kiln’s available oxygen is reduced. The path of ascent from monochrome to multicoloured glazes is evident on the surfaces – the same direction that his drawings took towards his paintings.

As he matured, Edelstein felt satisfied that he had struck a significant combination of his intuition and certain rational calculations, two elements that he felt should coexist in a work of art.

“Synthesis or abstraction always starts from something: first you have to know the world, in detailed observation, know the breadth of the panorama, as much as possible, master the techniques, that is, enrich yourself with experiences, so that later you can do without the superfluous, for when that can be eliminated, what remains is the essence. In this way, the expression is more just, more accurate and more equitable. For this reason, the controversy between the abstract and the figurative, for me, doesn’t make sense. In my view, the human form is the most sublime. This is why eliminating the image of man, human facial expression, that’s to say, the portrait, is an enormous loss. Geometry also has aesthetic qualities, but it never matches the emotion derived from seeing the human form. Naturally, in fine art, it’s not as it is in reality, but rather it is a metaphor, a rendition through memory, drawing or as in sculpture, the three-dimensional impression achieved by capturing the subject on a two-dimensional plane seen from various angles. This allows a return to three-dimensionality, in the final realisation based on the sketches for the final drawing. In this sense, in none of the portraits I made did I pose the portrayed model, but through previous drawings or photographs, and, later, through memory and emotional responses, I reconstructed and captured the image.”

The outcome of this entire stage was perhaps his last major exhibition, held in the Cronopios Hall of the Recoleta Cultural Centre in 2007, where he presented sheet metal sculptures. That grouping represented for him the culmination of his efforts as a fine artist. “I think I have managed to give meaning to long years of searches and explorations until I found a synthesised image”, he wrote for the exhibition catalogue.

Teaching

There is a photo from 1957 of the ceramics workshop that Pablo Edelstein taught at the Manuel Belgrano school: he is a young man with a serious but passionate appearance, attempting to conceal a smile among a small boisterous group that is laughing and celebrating around a student who is showing a great piece. They are all dressed elegantly, wearing ties, and Pablo wears a smock over his suit.

One great chapter in his life was teaching fine arts. He taught at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes for more than three decades, with many of his students later achieving notable careers. He began teaching art in 1947, when Lucio Fontana3 left for Europe, taking on some of his students. He continued teaching at Altamira, surrounded by other illustrious teachers.

In 1955, with the fall of Perón, the students of the art institutes revolted against the teachers, leaving these schools in a state of abandonment. His friend Raúl Russo was appointed auditor (by the newly formed government of the Revolución Libertadora) of the Manuel Belgrano school, which at that time was located on Cerrito street in front of the French embassy. Said Edelstein:”They filled me with hours of teaching, and I discovered that I had a great didactic and educational calling. Since then, I’ve had the conviction that the vocations of teacher and artist are inseparable for me. I have learned through doubts, questions and queries from my students and, as a consequence, I feel I have received from them, perhaps more than what I have been able to give them. Teaching forces one to be coherent, to be open to different temperaments and interpretations and needs, because each student is a world in himself.” Through a competitive process, in 1958 he obtained the official appointment to the position, going to teach at that school until he retired in 1989 at age 73.

During that time, he also gave classes in his studio – along with teacher improvement courses in Argentina and abroad. Among his correspondence, there is a letter from 1980 sent by the director of Miami Dade College thanking him for his presentation and lecture at the school, and another from the same year from Florida International University.

“I have learned a lot in this constant challenge. Because you must always teach by example. For that, I have always worked in front of the students, explaining what I was doing, and also recognising mistakes and failures”, he said.

“I learned the meaning of art with him”, said artist Lydia Zubizarreta, who was his student for more than 10 years, starting when she was 20 years old. “There were just a few of us and he was always there. The National Radio station was always on, or he played his jazz or classical records. He did his work, examined ours,returned to his work again, and never seemed to get tired. He liked the model in movement. We did quick poses of 10 minutes, or five minutes, and longer ones, 20 minutes.”

“It was always an adventure. His attitude never changed. It was always like the first day. He had an enthusiasm… like a boy, as if he were a student himself. He said he didn’t want to be a professional, because he thought he needed to devote all his time to learning. The moment of enjoyment was that of doing”, Zubizarreta recalled.

“When he didn’t know what to use, Pablo would add violet and the rest of the colours worked. But one day he entered and said that Nena had told him that he didn’t sell as much because he used a lot of violet”, Zubizarreta said with a laugh. She also treasured visits to exhibitions with other students to museums and galleries. “He explained things to us that we couldn’t see yet. ‘Dada, pop… the rules are meant to be broken,’ he said. He hated everything that was overly structured.”

Zubizarreta added: “He was always happy; in the studio, he was in his environment. He talked, he expanded, he loved talking about art. He conveyed art. He was very vital. He had a wonderful youthfulness. If he had to correct you, he would, but in such a nice way that you could never get angry at him.”

Edelstein was an extraordinary teacher: he invited his students to tea at his home. He organised outings to see exhibitions or to draw in the Botanical Garden. He took them to visit artists’ studios. He even purchased the works of his students at their exhibitions. “He wasn’t so interested in technique as in us discovering our own style through work. He guided us and gave us a lot of freedom. He taught me the different ways to look and see things”, recalled María Martha Pichel, who also took his classes for more than 10 years. “He was very generous. He gave me boxes of pencils, watercolours and paper. He was like a prince, a lovely person, always impeccable, a gentleman. He exchanged works with us, then, when we visited his home, we found ours hanging next to other pieces of his collection – which was excellent. He had a warm friendship with everyone”, she continued.

“Pablo was a different artist, he combined unlimited generosity and a sensitivity that was easy to discern in his eyes and hear in his voice. He gave us direction without demands, without criticism, with love and patience. He was very profound, he immediately knew what was happening in your soul, and if something went wrong, he consoled you. He was a great teacher. Humble and great”, said artist Marizú Terza, who attended his workshop for seven years. “I made ceramic sculptures with him and live-model ink drawings. I have more than 10 folders full of the work I did there. The sessions were very fast, dizzying: the poses might only last two minutes! He brought in black models, couples in romantic poses… it was very lovely.”

Edelstein had his reasons for working side-by-side, on equal terms with his students. “For me, the work is fundamentally a testimony, meaning that the work is a manifestation of life experience and, as such, it is enriched when one knows the art of all periods. The important thing is not to believe that you are the owner of the truth, but that, together with the experience of others, one enriches and refines that experience in the sense of keeping with the essence”, he said in an interview with the artist Alejandra Padilla. “I have learned by observing the work of the students, and I have received from them as much or more than I have been able to give them. I have always worked with the students on a par, at the same time, in front of them, even pointing out errors or corrections that one sees in one’s own work. You can’t teach what you can’t demonstrate”, he told her.

Legacy

One afternoon, sitting at the dining room table, Edelstein told his grandson Alexis how he understood life in art: “I never sought momentary success, which rarely happens in the life of an artist, and if it happens, the impact is limited in time and then no one will remember. I think I can leave a testament of how I lived, worked and my beliefs. I don’t have anything more to ask of life, but I can still give.

“I myself have changed styles, expressions, themes, techniques and materials, but reviewing my work, seeing what I have, I am rediscovering that everything underlies the same conception of the world and of existence. Because I do not consider life as an isolated existence that ends with one’s death or that translates into a quest for the salvation of the soul, but rather in the survival of the human species. And a work of art is precisely a communication, a message and a lesson for future generations to continue thinking as if we were a chain, one in which each of us is nothing more than a link. And this chain must not be broken.”

His interest was to create work that was transcendent due to the richness of its means of expression – not to be influenced by marketing or fashion, to exercise critical sense and be authentic, to achieve a universal and timeless value.

He did not seek personal success, momentary gratification, awards or fame. Edelestein worked to leave a testament of his life, his thoughts, and his aspirations for future generations. “I try to ensure that the work that is in my possession remains in the hands of my children, my grandchildren4, so that tomorrow they can exhibit it, but above all, as a lesson of how I have acted and worked. I never considered my work as a product or as a negotiable object. Yes, it’s true that artists’ works must reach the public immediately. But there are artists for whom their greatest desire is to reach the public to make themselves known, and thus enjoy a measure of prestige. I work so that my art is coherent, ordered, registered, so that it is not lost. I work every day looking to perfect my art and making it more understandable”, he said.

He lived the end of his days as if each one were the last, casting aside the insignificant, the superfluous, and the petty. He lived fully. Swimming daily to stay limber. Until the end, he worked using all his energy, strength, and lucidity. “It’s not success I’m after, but affection and appreciation, even from a few”, he said. He has been loved very much, by very many, and he has left for them, and for everyone, a valuable work.

Pablo believed that the human being progresses ethically and morally to the extent that he loses fear: fear of losing the protection and affection of parents when he is a child, fear of God, fear of losing the love of a partner, that of children, fear of punishment, fear of illness, ageing and death. In his words, “Losing all these fears and overcoming them means maturing morally and becoming an ethical being, a content being, a useful being in solidarity with others, doing good, and in this way possessing true and supreme love.”

In this harmoniousness, he lived and created. Always having a project, something that kept him tethered to the present and challenged him towards the future. He kept driving his Ford Taunus until he was 87, until his son removed a part from the engine because he simply wouldn’t surrender his driver’s licence even after suffering two strokes (from which he recovered). He gave the car to his computer teacher, whom he saw each week, always keen to learn something new. He never stopped working.

His last studio, at 689 Catamarca street, was set up as if he were going to return at any moment. One winter morning, I wait at the door of this old high-ceilinged house for his grandson Alexis to come and open the door for me, thinking, it’s okay that he’s late because his grandfather wasn’t punctual. Meanwhile, I lean on the doorway, imagining how many times Pablo had crossed it. I have the sun to keep me company, and a sparse tree, and I think also his kind ghost. Writing his life has been a beautiful task. I put my hand in the pocket of the coat that I haven’t worn for a year and find the calling cards of one of his dear students and another from one of his art dealers. I laugh silently with the artist. It has to be one of his jokes.

I discover a small table upon entering, with elegant dining chairs, a desk lamp, a pen with thick pencils, like carpenter’s pencils, markers and more pencils. Along the walls is Nena, young and beautiful, in drawings, paintings and busts. Behind her is his prodigious library of thick, cloth-bound books. The entire history of art fitted into those precious glass-fronted bookcases. The more-than-one hundred volumes of the Enciclopedia Espasa Calpe are there – when one of his children asked a question during lunch, it was always on hand for Pablo to read them an answer.

He loved those talks with his children, sharing his love for culture. When they were grown, he kept clippings of interesting news items to chat with them about when they visited him. He was also willing to express his emotions. On each of his birthdays, he took the floor to thank each one for their presence in his life. He cried with joy when he saw his children’s cars roll up with his grandchildren inside at the summer house, and with emotion when, in the company of his children, he visited the hotel where he was born. Always ready for joy, if the music of Zorba the Greek was playing, he would ask his son to dance in the middle of the living room. He once travelled with his children and grandchildren in a motorhome to Rio de Janeiro. Everyone remembers him on the roof, with his little chair and his pad, drawing landscapes. On other trips, he would sneak off to museums and galleries.

I discover his music equipment, which never tired of playing. On every wall in this house is a shelf for busts and statuettes, the paintings reaching to the very high ceilings. I imagine the artist at the back, working in that large kitchen, the natural light streaming through the windows and translucent half ceiling. His stocky, sturdy marble-topped table is bare; running a hand over its surface, you can sense the years of work it endured in its lines, cracks, and scratches.

Every box Alexis opens contains a treasure. We go through letters, documents, gallery guest books filled with praise and affection, newspaper clippings, family photos and photos of people that he studied for busts. I am taken by the photo where he is seen in deep concentration, his hands on a piece atop a pedestal, his pipe firmly between his lips, a long-sleeved shirt, and his blond hair combed back. He would be my age in the photo, neither young nor old. I am touched by the painting from 1933 where he is dressed to ride, 16 years old with all his future in front of him, but that happy and positive look is already there. He is already a rider who doesn’t fall, who isn’t afraid.

I stop upon finding one of his famous sketch pads and: a live model session from August 23rd, 1976, fills the pad, sheet after sheet the model changes position. I also see on the paper his ink-tained fingerprints. There are seascapes and nudes in another smaller sketchbook; I imagine he travelled with it one summer.

On one wall I see a tribute that arrived in time, a Diploma of Honour awarded by the Argentine National Senate in 2009 for his contribution to culture. His most recent work, the last one, a collage triptych on sculptures by Antonio Canova, the Italian sculptor and neoclassical painter; he finished it a few days before his death on October 22nd, 2010, at the age of 93.

“He always had a project ahead of him, something to create or investigate. I think

that’s why he had such a long life”, says his son Pablo. In the hearts of his two children, with whom he shared a close relationship, his most important lessons are indelible: the end never justifies the means because the means and the process are much more important than the end; following one’s calling is not merely an option, but the only way to achieve happiness in this life; life is not borrowed, but lived fully with every moment enjoyed; feelings are not to be filtered, but allowed to flow fully, whether positive or negative; wealth that is truly valuable and endures is spiritual wealth. At his 90th birthday party, he was still dancing, laughing, enjoying… living each one of his principles, embraced by his family’s love. A harmoniousness he knew how to nourish. All his work remains as a testament.

Sources

“No aconsejable para cardíacos”, article in Gente magazine, November 1966 edition / 40 Escultores Argentinos. Ediciones Actualidad en el Arte, Buenos Aires, 1988 / Blum, Sigwart , Pablo Edelstein exhibition catalogue at Martha Zullo, September 1977 / Pablo and Verónica Edelstein conversations and recollections with the author, July 2021 / Correspondence of Pablo Edelstein and Lucio Fontana / De Carli, Ernesto. Crónica del Centro Argentino de Arte Cerámico, 1958-1998 / Alexis Edelstein video interview with the artist Pablo Edelstein / Verónica Edelstein interview with Pablo Edelstein, her father, Buenos Aires, 31 July, 2002 / Author interview from June and July 2021 with former students María Marta Pichel, Lydia Zubizarreta, Alejandra Padilla and Marizú Terza / J. Linares, “Edelstein at Martha Zullo”, Pluma y Pincel, October 1997 / Jornadas Internacionales de Cerámica Contemporánea, 2006, Honouree Pablo Edelstein address / Larravide, Ana, “La conquista del espacio y del tiempo”, revista Cerámica, April 1993 / Luna, María Gabriela, “Cerámica y arte contemporáneo: Una dura trayectoria en proceso de consagración”, IX Jornadas Nacionales de Investigación en Arte en Argentina, Universidad de la Plata, 2013 / Pablo Edelstein. Esculturas en chapa metálica (cat. exp.). Buenos Aires, Centro Cultural Recoleta, 23 February to 18 March, 2007 / Pablo Edelstein. Esculturas, (cat. exp.). Buenos Aires, Galería Rubbers, 15 to 29 April, 1970 / Pablo Edelstein. Pinturas y terracotas, (cat. exp.). Buenos Aires, Galería Martha Zullo, 18 September to 9 October, 1980 / Padilla, Alejandra. “Entrevista al artista plástico Pablo Edelstein,” Monograph. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2007 / Video recording of the artist at work, by Claudia Sánchez / Video of the artist’s 90th birthday celebration by publicist Carlos Pugliese / Villaverde, Vilma. Arte cerámico en Argentina. Un panorama del siglo XX. Editorial Maipue, Buenos Aires, 2014 / Visit to artist Pablo Edelstein’s studio: works, documents, photographs, visitors books, sketches, certificates, notebooks, books and letters, property of the artist / Whitelow, Guillermo, “Edelstein: Poetry and Reality”, June 1988.